This year’s Biennale Arte, entitled: “May You Live In Interesting Times,” proved to be about anticipation – from the very moment Ralph Rugoff was announced curator, and we all held our collective breath awaiting his curatorial decisions, to those ‘interesting times’ passed in the never-ending queues outside the pavilions. Viewers patiently spent hours conversing, making new friends, and eagerly awaiting feedback from those fortunate ones leaving the shows, seemingly hypnotised, and shouting: “It’s worth the wait!”.

According to Biennale President Paolo Baratta, ‘interesting times’ evoke the idea of challenging, or even menacing, times. Sir Austen Chamberlain first referred to what he thought was an ancient Chinese curse, in one of his 1930s speeches, having, apparently, picked up this expression from a British diplomat who had served in Asia. Curiously, a Chinese source referring to the curse has yet to be located, which unfortunately, fails to negate that the aforementioned times have, indeed, befallen us. In turn, Rugoff chose to reference the British MEP in order to underscore the current age of spurious news, and disinformation – asking one and all to “pause whenever possible” and “reassess our terms of reference.”

But, back to ‘anticipation’ – almost everything presented at the Biennale was about waiting for change, as a result of which the world would become a better place. In fact, Rugoff referred to artists as guides who should consider themselves indicators of potential, and upcoming, dangers, and to art as a “means of noticing”. Artists carrying social responsibility, which includes both investigating critical matters and raising awareness through the language of freedom. “…in an indirect fashion, perhaps art can be a kind of guide for how to live and think in ‘interesting times’,” voiced Rugoff, who cutdown the number of participating artists, and asked each one to show two different pieces – at Giardini and Arsenale, giving them an opportunity to showcase a broader range of work, as well as a larger audience to focus and explore the fruits of their labour. Without any further spoilers, ZEITGEIST 19 would like to highlight the critical and impactful work of Korakrit Arunanondchai, Jimmy Durham, Shilpa Gupta, Frida Orupabo, Soham Gupta, Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Carol Bove, Khalil Joseph, Zanele Muholi, Arthur Jafa, Lui Wei, and Neil Beloufa. As for the national pavilions, we tip our hats to: Ghana, U.A.E., Lithuania, Poland, Denmark, Brazil, U.S., South Africa and Korea.

ZEITGEIST 19 interviewed some of the participating artists and curators of the Biennale Arte 2019 and its must see collateral events, whose work addresses social and environmental transformation, in order to further open a dialogue regarding how art can serve as a guide and how it reflects on the global framework, as well as upon the current times, and anxieties because apocryphal expression or not – it is certainly hard to deny that we do currently find ourselves in ‘interesting’ times.

Lorenzo Quinn, Sculptor, ‘‘Building Bridges’’

How are you responding to the time of Now with “Building Bridges”?

Everything I do is made to transmit a universal message. My previous sculpture was called Support, to raise awareness for climate change. But of course to do anything about climate change we need to work together. That is why I have made Building Bridges. To ‘build bridges’ is actually going into action. Let’s take action. Let’s do something about it. Building 6 bridges, each representing a specific symbol, such as hope, help, faith, wisdom, friendship and love. It is 6 because we have 5 continents and one of the bridges – “Love”, brings all together.

What is the transformative power of Art?

I believe Art has the power to transmit a very important and powerful message, which perhaps with words you cannot express. When you see something, it affects you. After placing the Support project I have received a wonderful compliment – people told me that it influenced their daily routines. The idea of change! Human beings can achieve fantastic things while working together.

Ralph Rugoff mentioned, “Art can be a kind of guide for how to live and think in ‘interesting times’.” Do you agree that an artist carries a responsibility in identifying and informing the public on current critical issues?

I don’t think that the artist is responsible for that but if he can do that, it is great. Art can’t solve all the problems of the world. We are people like anyone else, we just express our ideas differently. I cannot close my eyes for what is going on in the world, so whenever I have a chance to talk about it, I try to.

From tomorrow numerous amounts of people will be passing by your work. What kind of emotions do you hope to elicit? What do you hope people will take away from their experience?

I hope people will take away the positive message I try to transmit – breaking down barriers and communicating and helping one another. We are much stronger together. The human race has always evolved through communication between cultures. Venice is a perfect example for that.

Nujoon Alghanem, Poet & Filmmaker – U.A.E ‘‘Passage’’

Can you tell us more about the invented language in your work?

I have worked with an actress, who has her own practice and own vocal experience and skills. When we were rehearsing I wanted to record only the vocals. She started speaking in a strange language. People who don’t know might think it is a language, but it wasn’t. When we were developing the film and deciding the scenes and the content, we decided that it is going to be a new dimension, adding up something different. It doesn’t relate to geography or nationality. It relates to the human soul, to the human expression, to the human uniqueness. And when the protagonist reaches this frustration, she starts producing this song, expressing herself. It was necessary to highlight not the nationality of a language but an expression of individuality, without any labels.

What is the condition of the main character?

The protagonist goes through several challenges in life, similar to any of our challenges. Sometimes you see yourself as displaced in your own community, country, family or group. Sometimes when you are travelling, especially with the current situation and the preconception toward people of different nationalities. They treat you differently. You become a subject of oppression and all sorts of unfairness. You start to build your own cocoon and you start trying to protect yourself. A place for your soul, for your human being. Together with the curators, we all agreed that this piece has to reflect on universal subject matter and what is going on right now. We tried to express that in a subtle way, without shouting, without accusing anyone.

It is a sensitive and beautiful work. Is it site-specific for this Biennial?

It is only for this Biennial and from the beginning the curator felt that the best for the space is to have a double sided screen. We had to create a content that fits this space. That is how we started developing it.

How does it feel to be a part of La Biennale di Venezia?

It is a great honour. It is a dream for any artist. I have mentioned in my speech that I came to Venice in 1955 as a student. I have studied art history and I visited Peggy Guggenheim museum and I saw Giacometti’s statues there for the first time in my life. I had a very secret wish – to be able to exhibit in this city. In 2017 I took a very small part at U.A.E pavilion and this year I have the opportunity to be the solo artist. It is a huge honour to work with very intelligent people. The whole team added a lot to the project. And I hope that it will keep receiving good response.

You are a practicing poet, and you use your poem in the current work…

Yes, I have published it in collections of poetry books. It is a modern poem, which wasn’t welcomed back then when I wrote it. It is a very personal piece, that relates to my world. Poetry is a language that you should share with people. And because this film has sections, we thought we needed another narrative, another layer to weave the story. And poetry created this new dimension.

Nomusa Makhubu, Curator – South Africa ‘‘The Stronger We Become’’

How does the South Africa pavilion represent the times we live in?

Titled The Stronger We Become, the South African pavilion focuses on the disillusionment of the post-1994 era. With rising social unrest, protest, and social movements, South Africans are compelled to look back (at our unforgiving history) and look in (at ourselves). Faced with retribution in the moment of our retrospection and introspection, we are immersed in the contradictions of contemporary life. South Africans are navigating globally entangled, racially-defined, socio-economic issues. And this requires from us resilience and resistance. The three artists, Mawande Ka Zanzile, Dineo Seshee Bopape and Tracey Rose pose critical questions about human dignity, knowledge and power, loss and displacement. We are experiencing a change in global politics, as the world seems to become more conservative, more localist. In this spatio-temporal fix, we look back at the impact that previous policies have on our present and futures and uncover the sense of global nihilism.

Do you agree with Ralph Rugoff statement that “An exhibition should open people’s eyes to previously unconsidered ways of being in the world and thus change their view of that world.”?

Well, yes, but we, as artists, curators, and scholars have more responsibility than that.

We are in search of re-enchantment and re-defining the world today. Can artists help us in re-shaping our perception?

Yes, but artists can also organise socially. Indeed, we are searching for re-enchantment but the quick regression to disenchantment often becomes like a vicious cycle – akin to what Lauren Berlant calls ‘cruel optimism’. To find re-enchantment is to sustain a public, socially engaged life.

Can Art be really free and independent?

To a certain extent. And also not while it is tied to the cadence of plutocracy.

Nana Oforiatta Ayim, Curator – Ghana, “Ghana Freedom'

“Ghana Freedom' is Ghana’s first national pavilion at the Venice Biennale. What does it mean to you and what would you like to address with it?

It means a lot for us to have our first national pavilion at such a narrative-building event as the Venice Biennale, especially at this moment. The conversation about nations is broadening in the face of issues of migrations; of us redefining our connections to our diasporas throughout our ‘year of return’; of discussing what it might mean to have our cultural objects returned, and how we thus might redefine ourselves in the world; and of finally moving out of the ‘postcolonial’ moment into one we have yet to envision.

Marcos Lutyens, Artist, ‘‘Island Arc’’ Solo Show

What are the compartments of our times you have decided to examine with your latest solo show? What ideas and concepts do you embrace in it?

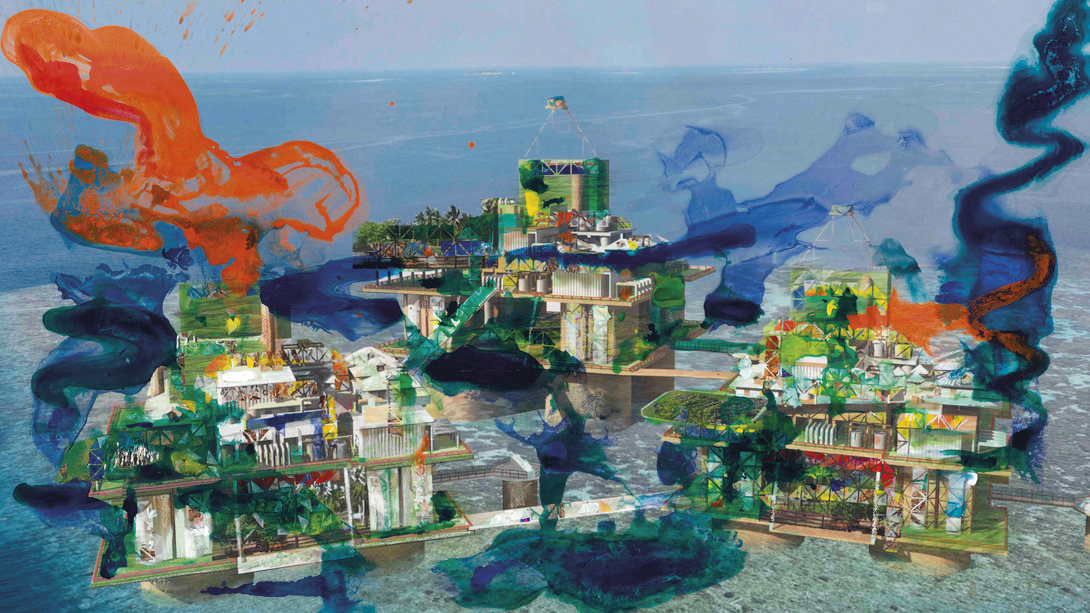

The Island Ark project responds to the single biggest threat to us, over and above political strife and economic uncertainty, which is climate change and its associated effects of sea level rise. Recent reports state that by the year 2100 sea level will have risen 2 meters, which will put many areas that are currently inhabited under water. The worst affected places are low lying island nation states, such as Tuvalu, Kiribati or the Maldives. The core idea of the project is to move a disused oil rig to one or more of these islands or atolls, so that there can be a way of preserving the community once the islands have disappeared. Before the islands are lost completely, it’s not just a question of providing the ability to conduct scientific research or shelter from cyclones, but rather to help preserve the local cultural heritage and traditions, as well as to anchor the increasingly dispersed diaspora to a location of origin.

Your work is centered on the visitor’s experience. How do you expand our ‘scale’ of sensitivity and intensify the experience of life?

Two works involve the visitors to the Island Ark exhibition. One, called Means of Flotation was a performance that I conducted twice (and also once at My Art Guides, Venice Meeting Point at the Navy Officer’s Club), which involved participants in a trance state dipping their feet into 4 different colored paints. Each color had its own psycho-emotional sensation which would extend upwards through the body. The participants ended up drawing shapes related to their emotional states automatically, or unconsciously on their yellow boots. Another work which is ongoing until September, called Table Salt, involves participants drawing ideations related to sea level rise with their fingertips onto a table that has a surface made of salt. Both projects sensitize the participants to connect to their surroundings, in this case related to the ocean.

What can artists do to fight Climate Change or to create social transformations?

It is essential that artists help draw attention to the urgent need to fight Climate Change. The only really effective front for fighting this is by starting with people’s consciousness and then changing their attitudes and behaviors. This must be done world wide in a concerted effort by artists working with all walks of life. Artists can help scientists too, to express their research and findings and get the word out, since science is sometimes a difficult subject to communicate to every day people.

A focal point of your work is investigating consciousness. What parallel approaches do you try to incorporate into art and how hypnosis and meditation can change our perception and encounter with the anxieties today?

There is generalized anxiety in our societies across the world. Things are changing faster than ever before in terms of the workplace, environmental threats, polarizing politicians, wars and famine. Focusing inwards through meditation or hypnosis can help to balance one’s sense of self and being in the world, and help nudge us towards healthier ways of taking part in this world. The conscious mind seems to be hell-bent on (self) destruction, so we need to look inwards to find a longer term perspective on things.

Interview by Farah Piriye, Elizabeth Zhivkova

Photo: press materials

The article was published in the 63rd issue.