He left Azerbaijan to significantly influence the St. Petersburg underground, live in refugee camps, spend the night in Paris workshops, exhibit in Munich, Hamburg, Berlin, Nice, Paris – and live his own destiny in art over and over again. In Leningrad, he collaborated with the “new artists” of Timur Novikov, including Viktor Tsoi, this creative group made wonderful projects with such famous masters as Cage and Rauschenberg. He makes collages with avant-garde texts, collects installations from garbage, makes automatic writings... In his 60th jubileum year Babi Badalov visited Baku to host his solo exhibition at YARAT Contemporary Art Space.

It is your first visit to Baku after ages…

Yes, 12 years…

What did you feel?

I was shocked. I studied in Baku for 4 years, I would know the city very well, but now I do not know it at all.

He used to dream of escaping his motherland Lerik. At the age of 15 he came to Baku, then abroad – got refugee status, settled in the center of Babel. Subsequently he said that he couldn't express himself in any language. And our conversation turned into an entrancing mix of three languages, sometimes within the same sentence.

Is it your first exhibition in Baku?

I would say it is my very first exhibition actually. I used to attend in group exhibitions many years ago. In 2002 or 2004, I had an exhibition in the Old Town, it was a success, but there was no statement in it, nothing of the topics and problems that I am raising now... It was just an exhibition. Now I do not do “just exhibitions”.

How was the idea of ZARAtustra born?

I understand that I have to bring something to my country – what I learned in France, what France gave me. I didn’t go there for a good life, not to have fun. I’m an artist, I have a creative mission.

Are you struggling with capitalism?

This is the concept of the exhibition. Baku shocked me on my first visit. When you arrive in an unfamiliar city, say, in Jakarta, you check into a hotel and at first, going beyond it, you are afraid to get lost. So, when I come to Baku, I walk a little... I do not recognize the city. Throughout Bailovo, I recognized only one high-rise building with a bus stop, everything else changed dramatically. This is all wonderful, but at the same time, I notice that capitalism has occupied the city: brands are everywhere, all buildings pay tribute to fashion, something is constantly being built... I don’t understand why so many new buildings, why destroy history? I like modernism, because time is modern, it is moving forward, but culture is a fragile thing, and it is very important. Culture is our identity, our duty is to protect it for future generations. If we lose our culture, it will be a loss for all humanity. For the French, I am always Azerbaijani, because even speaking fluent French, I speak with an accent. I think differently, imagine myself differently, I look different, even if I don’t differ much, I have a different opinion... For them, I am the man who enriches French culture with Azerbaijani one. For a long time, France was the centre of everything, everything could be found there – from impressionism to postmodernism, everyone wanted to move there, and it embraced all, everything there was boiling. This country is grateful to everyone who enriches its culture. Till today some people don’t know what is Azerbaijan, where it is located, for instance, they ask: “Abidjan? Is it the capital of Ivory Coast?” I am a French citizen already, I have a gallery in Paris, next to the Centre Pompidou. They like me there, my works go to collections of many foundations, museums...

Our essence is, as Paul Valerie said, a heaping pile of random facts, sensations, urges, incoherent words, fragmentary phrases – and from this chaos Babi Badalov's poetry is born.

In Paris, I live only one metro station from Montmartre, and there are many Senegalese, Malians, Algerians people. Every day I see so many different national costumes! Their women never dress differently. Very yellow, very green – they retain their identity, and I like it, it's great. I realized that I must confront the phenomenon of capitalism. ZARA is also a part of it. I am not against Zara, I do not say ‘no’ to it, but there is too much of it. Zara has become a kind of drug. For me, clothes should just be clean. Some women may disagree with me, but I am a feminist and do not separate men and women. There is too much capitalism in Baku. Neftchilar Avenue is not Azerbaijan. Yes, these buildings have many attributes of Azerbaijani culture, I like the Baroque style, it is much nicer than the faceless geometric modernism. I do not mind, but this trend is too aggressive...

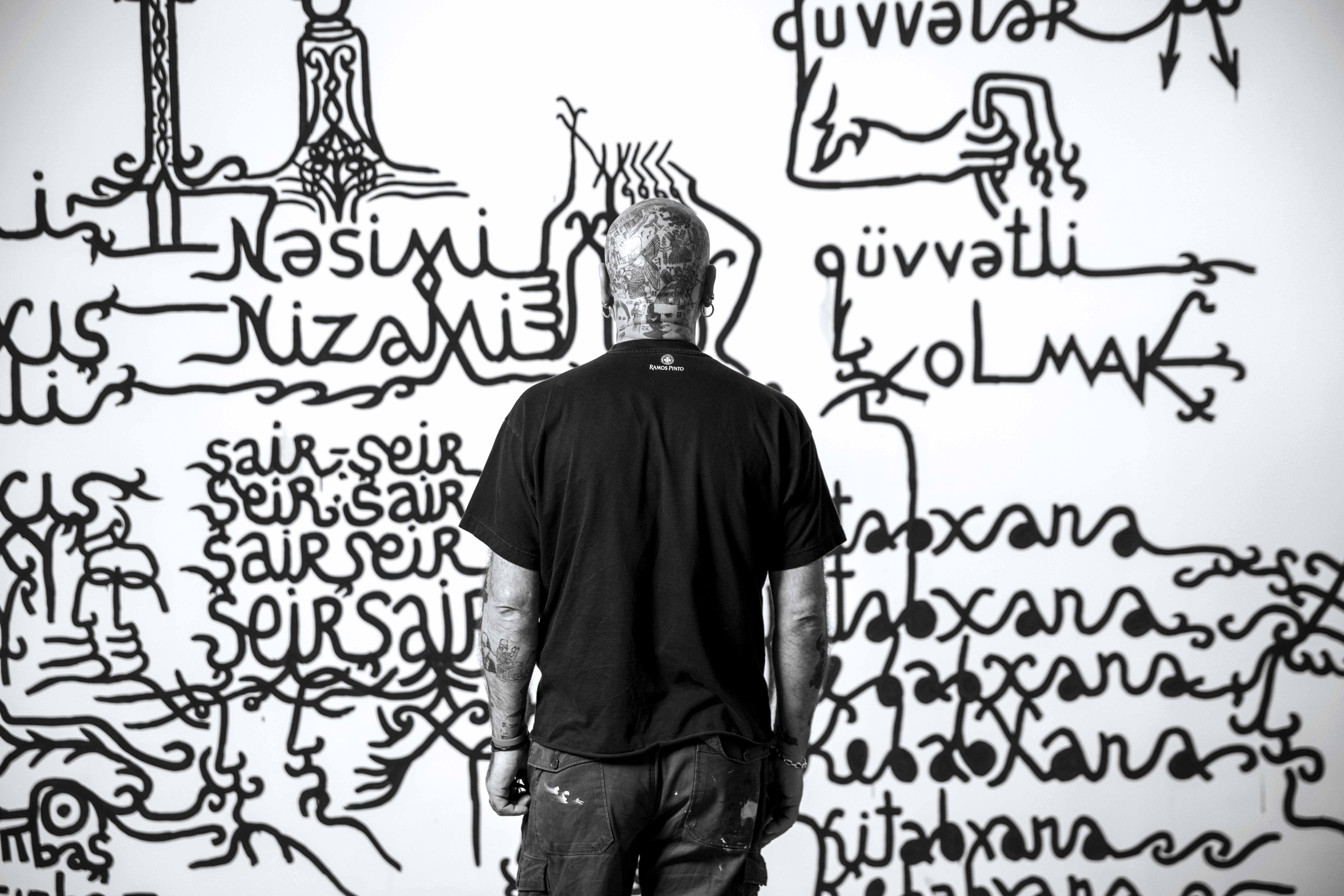

The installation called ZARAtustra includes old sheets hanging from the ceiling, fragments of curtains, fabric cuts with words, drawings, lines printed on them – about 250 textile cuts in total – and hand-written slogans and texts along the entire length of the gallery walls. The artist used the expressiveness of the language and visual images to create a three-dimensional postmodern work full of cleverly arranged nuances and socially charged puns.

Our country was occupied by the Arabs in the 7th century, before that we had Christianity, and even earlier – Zoroastrianism. This is our identity, we have architecture, books, Surakhany, Maiden Tower, the tradition of ‘Od Chershenbesi’. We were converted to Muslims, our rulers converted to Islam, and we gradually lost our primitive history. At ZARAtustra, Zara stands for the present of capitalism and Zarathustra stands for our past, came together in contrast.

If a literary critic discusses the density of the poetic series, then the visual poetry of Babi Badalov is akin to the superdense point of the singularity that preceded the Big Bang. “Word-making is an explosion of linguistic silence, deaf-mute strata of the tongue,” Velimir Khlebnikov wrote. The art of Babi is not a combination of techniques, but a manner of seeing the world, a manner of dealing with the surrounding and internal reality. He draws from the inexhaustible cultural resources of the language.

My exhibition is divided into three sections. The first is about capitalism, shopping centers, fashion. We decided to devote the second to orientalism, it is also ornamentalism: bəzək – naxış... (decoration – pattern). We are an Eastern country, in the essence of our country lies ornament, especially carpet ornaments. In France, my cultural identity is recognized by my ornamental designs. I included here the name of Edward Said – you may have heard of him, he is a Palestinian, academician who first described the theory of Orientalism. Edward Said described it – and I, the artist, decided to visualize it. When you see what is written, the form of the letters is not so important for you, the content that is understandable is more important, but I write and draw at the same time. It’s akin to calligraphy, but I call it visual writing. I am a text artist. You see a drawing – and you read it. Some canvases are two-sided, and one of the sides is exclusively ornamental, because it is impossible to read the text “from the inside”. I used a mirror effect. It reflects my Parisian migration and life in two languages, in Cyrillic and Latin script…

He learns the world of possibilities through languages, therefore his works are determined by him and are inconceivable without his creator. Paroles, paroles, paroles... He is in every letter and in every word, and their fluidity, temporality is akin to human mortality. In the beginning was the word: Heraclitus Logos, the Hindu Atman, also meaning “me”, “myself”, “I”... For Babi Badalov, the creative sign and the created sign are the same. He makes up for the visible mute, realizes his transcendental project, conceptualizing – and thereby appropriating – being. With his hands, the demiurge makes the transition from non-being to being, which, according to Plato, is creativity: there was no word, no rhyme – and now they are. Written, read, exist.

This is a very personal exhibition, isn't it?

My work is dialogue. It is very important not to mythologize art. For me, art is real, it is open to all. I’m talking about what and how I see... And we decided to devote the third part to the mystery of automatism, because most of my work is based on automatic writing. On the very automatic writing that the Dadaists invented in the 20th century.

Language creation is what Babi Badalov does. The self-creation of the tongue, its autopoiesis becomes visible, almost physically tangible. Perhaps the automatic writing of the Dadaists was the first conscious embodiment of autopoiesis in art. Perhaps it was it that Louis Aragon called the “internal music” of poetry, saying that “the meaning is formed besides you: the words, merging together, eventually begin to mean something.”

I had an exhibition in Portugal, and I created a manifesto for electronic Dadaism. This is a separate issue, I would be glad to return to Baku in a couple of years with a new exhibition or a small project devoted to the essence of automatic writing and electronic poetry. As the Dadaists preferred automatic writing to thinking, I use my phone. My poetry is based on randomly typed words.

Marcel Duchamp devoted a whole report to how the artist reveals the intrinsic value of a work without despotically inventing its final ideological idea, but gently and carefully leading the creative process to an unexpected embodiment. The next step is to decrypt the message by the viewer. For postmodernism, not only the creative process is important, but also where the work lives, because audience perception is part of the creation process. The many-sided contemporary art does not want to be named by name, limited in terms – each of us sees in it something of his own, to each of us it turns a special side. And this endless mysterious process makes the work of art immortal.

This wall, called Intervention, is designed specifically for Azerbaijan. If you want to have a dialogue with the whole world, you use English, but this wall is for Azerbaijanis, here are used words that the expat will not understand. This part of my heart is for Baku, in France I could not do this. My father is Azerbaijani, my mother is Talysh, but Azerbaijani is my native, first language. I like the way it sounds. Love of language brings poetic inspiration. Biri var idi, biri yox idi – ikisi var idi, ikisi yox idi... milli naxış – milli baxış... It is conceptual. Qarabağ – a word game, «look at snow». Ağa bax... Word games reveal the potential of our language, its melody, rhythm, beauty and rhythm modulation. I am very happy that this project has been implemented here, this is the documentation of my life.

Does the creative process make you happy?

Very! I am very ascetic and like to be alone, but in art I am a big activist. Art for me is power, it can bring happiness and peace. I create only when I am happy.

You answered my next question in between. We saw from the example of Russian cultural emigration of the 20th century that many emigrants cherished the main features of their culture that they knew. Time stopped for them. I was going to ask what you have captured and taken away from the culture of Azerbaijan. And then you started talking about Karabakh, and it seemed to me, I heard the answer: you took the music of Azerbaijani poetry with you on a trip, because our culture is very musical...

Yes, that is right.

Tell us about your tattoos. How long did it take you to get them all?

Two years. Here the Janissaries, I took their sabers from them and replaced them with flowers: no – to the war! Zoroastrian letters, a portrait of my mother, Urartu, Sufi, Rumi, Dostoevsky... My head is like a history book. I am an artist to the core, I love art. I don’t have money, and when I do, I don’t know what to do with them.

Do you feel free?

In France – very! Here – no.

In one interview you said: the more order and law, the less freedom. What is more important for you?

Freedom is very important to me. Physical freedom especially. I faced blackmail, they threatened me if I came to Baku. Thanks to YARAT for my safety. But I am who I am. I am real and do not try to please someone specifically.

Interview by Sona Nasibova

Photo by Parviz Gasimzade